|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

Humans reshaping the environment. As populations grew, towns and cities gobbled up surrounding countryside, and the expansion of farmlands and pastures cut ever deeper into forests and grassy steppes. Deforestation was particularly rapid in tropical regions, as foresters felled timber to supply local and international demand, and farmers cleared land for cash crops such as coffee. Land erosion was another growing problem, particularly where migrant farmers tilled soils that were more fragile than they understood. This was the case with the creation of the “dust bowl” in the United States in the 1930s. Animal species suffered on land and sea. The total fish catch rose from about 2 million tons in 1900 to about 15 million tons in 1950. Consequently, fisheries from the North Sea to the Pacific began to collapse. The spread of technologies pioneered in Big Era Seven magnified the individual’s average environmental impact because men and women consumed more energy and resources while producing more waste. People used more and more coal, but oil production rose even faster to generate electricity and to feed the new internal combustion engines that widely replaced steam engines. Waste products from the burning of fossil fuels reduced air quality, particularly in big cities such as London and Chicago. In the course of the era, millions may have died from the effects of air pollution.

Between 1913 and 1950, the world’s total GDP almost doubled, while output per person rose by almost 50 percent. Near the end of the era, humans acquired a new source of energy, nuclear power. This source was so potent that, in theory, it gave humans the ability to destroy much of the biosphere within a few hours. For better or worse, human impact on the environment increased more sharply in this era than ever before. Indeed, humans became a major force for change in the biosphere. This is why some scientists now argue that we have entered the “Anthropocene,” a new geological area in which humans are the most important single force shaping the biosphere.

|

| Eastern Europe | 1.14 |

|---|---|

| Western Europe | 1.19 |

| Soviet Union | 2.15 |

| Japan | 2.44 |

| United States | 2.84 |

| Latin America | 3.43 |

The most powerful growth stimulator, however, turned out to be rearmament for war. By the late 1930s, all the major economic powers, including Japan and the US, as well as European states, were engaged in massive arms buildups. This fueled growth, but it also reawakened old rivalries.

The Great War. The two world wars together were a major cause of change in the global distribution of power. The wars had many causes, including competition for markets and colonies and a centuries-old tradition of military competition among European countries. In the late nineteenth century, the major industrialized states used their increasing economic and technological power to build up stocks of modern weapons such as machine guns and battleships. They also prepared for war by forging alliances that committed each country to the defense of its allies. The dangers of this system became apparent when Archduke Francis Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in June 1914. Austro-Hungary consequently invaded Serbia, Serbia’s ally Russia mobilized against Austro-Hungary, and within weeks the whole of Europe was embroiled in war.

World War I proved more horrifying than anyone could have imagined, and it demonstrated the colossal destructive power available to industrialized states. The conflagration showed a dark side of the modern revolution. Machine guns, long-range artillery, and mustard gas killed soldiers by the millions. Aircraft strafed and dropped bombs on soldiers and civilians. These weapons worked so well in holding defensive positions that decisive attacks were almost impossible. On Europe’s western front the war settled into a grisly, prolonged siege in which soldiers assaulted enemy trenches only to be mowed down.

On the home fronts of all the states involved, the huge power concentrated in modern governments and industrial economies was harnessed for the fight. Warfare became “total,” as governments took control of much of the economy in order to mobilize their populations and resources. Civilians played as vital a role as soldiers and also accounted for an increasing number of casualties. The war also transformed the lives of many women, who had to manage all aspects of domestic life when men were away and who took over men’s jobs in munitions factories and other branches of production.

Because the rivalries that caused the war were worldwide, so was its impact. The Ottoman Turkish empire joined World War I on the German and Austro-Hungarian side. French, British, or Japanese forces seized German colonies in the Pacific and Africa. Troops from French and British colonies in Asia and Africa, and from former colonies such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand fought on the British and French side. In 1917, the US entered the war against Germany and its allies. US supplies, troops, and money, together with the huge economic and agricultural resources of the British and French empires, eventually tipped the balance against the central European powers. On November 11, 1918, Germany signed an armistice.

Soldiers carrying a wounded comrade away from the front lines, Western Front, France, 1917. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog Reproduction #LC-USZ62-98917 |

|

|---|

By then, 15 million soldiers had died and another 20 million had been injured. Millions of civilians died as well, and destruction of infrastructure, industries, and farmland was colossal. The end of the war left the liberal capitalist system facing many daunting challenges.

The Paris Peace Conference (1919) stripped Germany of its colonies and saddled it and Austria with the burden of paying reparations, that is, much of the cost of the war. It also created the League of Nations, the first fledgling world deliberative body, whose primary mission was to prevent future military catastrophes. The League had little independent power, however, and the punitive peace treaty of 1919 ensured that Germany and Austria would continue to nurse resentments.

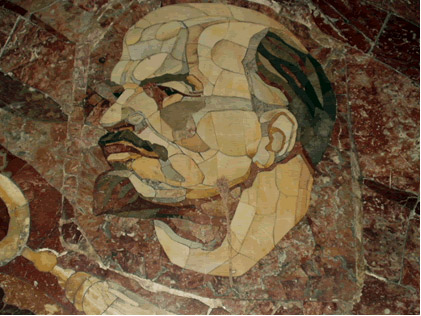

Vladimir Lenin depicted in a mosaic on a wall in a Moscow metropolitan subway station. The portrait dates to the 1930s. Photo by Ross Dunn |

|

|---|

The rise of the Soviet Union. In Russia the creation of the world’s first communist state posed a challenge to the entire capitalist system, a challenge that would last until the 1990s. In the late nineteenth century, the Russian Empire tried hard to industrialize to keep up with the rest of Europe. However, the strains of rapid economic change combined with the war, which saw a German invasion, undermined the autocratic government of Tsar Nicholas II. In February 1917, he was forced to abdicate and to leave the country in the hands of a weak “provisional government.” Into this political vacuum stepped the Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin (1870-24). As a Marxist, Lenin had no use for nineteenth century-style liberalism, and he was convinced that the war signaled the collapse of both capitalism and imperialism. He believed that Russia would pioneer a new and better type of society, one that would do away with the political and economic inequalities of the capitalist world order.

The Bolsheviks unilaterally pulled Russia out of the war, won a civil struggle against internal enemies, and expelled most of the country’s capitalists. They were left, however, ruling a country, now the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, that was poorer and less industrialized than it had been ten years earlier. Before they could realize communism, they argued, they would have to rebuild Russia’s economy. In 1929, Stalin, Lenin’s successor, launched a radical, state-led industrialization drive. He used planning techniques pioneered by wartime governments and much of the technology invented in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, from railways to radios. He ruthlessly seized Russian peasant lands, thereby eliminating the last remaining bastions of capitalism.

The strains and costs of compulsory industrialization were great, including a massive famine, creation of forced labor camps, and political purges that by the 1930s cost the lives of several million people. Even so, Stalin’s brutal methods produced a powerful industrial economy. This success inspired some political leaders and revolutionaries in other lands, including western European countries and their colonies, to take up the Communist vision of the future. Though communist movements made little headway in most places, the Communist leader, Mao Zedong, achieved victory in China. On October 1, 1949, he announced the formation of the “People’s Republic of China.” This meant that about one third of all humans lived under Communist governments.

Fascist governments. In Germany, Adolph Hitler’s ideology of ‘National Socialism’ (Nazism) offered a second authoritarian alternative to liberal democracy. Nazism built on the sense of despair that World War I, the Depression, and the punitive war reparations caused among Germans. Nazism offered an extreme version of the competitive nationalist ideologies that had led to the war. Hitler became an advocate of fascism, an ideology that saw politics in terms of racial conflict between different nations, championed authoritarianism, and despised liberal values. The Nazi party flourished, and in 1933 Hitler became Germany’s leader. Exploiting international disunity and the weakness of the League of Nations, which the United States never joined, Germany threw off the Versailles Treaty’s penalties and restrictions and began to rearm. As in other countries, huge government expenditure for weapons was just the stimulus needed to revive the German economy. This in turn boosted Hitler’s popularity. Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), Hitler’s fascist ally in Italy, embarked on a similar program of nationalist rearmament. Fascism found other imitators as well, for example, in Spain, Brazil, and Lebanon.

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938), the Turkish military officer who led Turkey to independence in 1921. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog Reproduction #LC-USZ61-620 |

|

|---|

Nationalism in the colonized world. In colonized regions of the world, nationalist leaders began to challenge European control, many inspired by the liberal democratic traditions of Europe and the US, some inspired by communism and fascism. World War I destroyed the empires of Germany, Austria, and Ottoman Turkey. Germany’s colonies and Ottoman territory in the Middle East were taken over by France and Britain as “mandates” or “trusteeships” theoretically under the League of Nations. (The German colony of Southwest Africa was turned over to South Africa as a mandate.) Consequently, the British and French empires not only survived the war but became even bigger. However, Turkey, the heartland of the former Ottoman empire, emerged from the war as an independent state under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Nevertheless, nationalist movements for reform and independence began to come together in the colonies. In India, the Indian National Congress, first established in 1885, became a powerful supporter of independence. In Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948) it found an inspirational and creative leader. His non-violent protests against British rule played a crucial role in achieving independence in 1947. In parts of Africa, too, new educated leaders, including Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, and Julius Nyerere, emerged, and in the aftermath of World War II they began to demand total independence. In China and Vietnam the anti-imperial rhetoric of Soviet communism provided the inspiration for the nationalist leaders Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh. In all those regions, intellectuals, artists, and politicians wrestled with the fundamental fact that the modern revolution had arrived in the form of European colonialism, unfavorable trade relations, and European ideas of progress. These women and men were determined to advance modern technology, science, and political organization but equally set on finding ways to do it that were true to their own national traditions and aspirations.

Challenges to democracies. The major liberal democracies were by no means immune to new problems. Governments were pressed to take their own liberal rhetoric more seriously by extending the vote to larger sections of the population and to women as well as men. New Zealand granted the vote to women in 1893, the first sovereign state to do so. The United States and most European countries followed only after World War I. Socialist parties also challenged governments, particularly during the Great Depression, to tackle the inequalities that were still widespread in democratic and wealthy nations.

World War II. All the challenges of the 1920s and 1930s led toward a new round of conflict. In some sense, World War II was a continuation of the first war. Japan, seeking to create its own empire in East Asia, invaded Chinese Manchuria in 1931 and mainland China in 1937. Fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935. In Europe, Nazi racist belligerence and aggression against its neighbors, first Austria and Czechoslovakia, then Poland, led Germany in 1939 into war with France and Britain.

The rail line that brought prisoners to the Nazi concentration camp at Terezine in northern Czechoslovakia, today the Czech Republic. Photo by Ross Dunn |

|

|---|

The conflict soon became global. Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, and Japan, Hitler’s ally, attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. World War II was fought in Europe, the Soviet Union, North Africa, West Africa, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Eventually, the sheer weight of resources and human numbers ranged against the fascist alliance made the difference. Britain and France fought with the support of both soldiers and civilians from colonies and former colonies throughout the world. The US concentrated its wealth, industry, and citizenry on the war effort. And the Soviet Union mobilized huge human and material resources with brutal efficiency. The Allied Powers invaded Germany from both east and west in 1945, and Hitler died in his Berlin bunker. Japan surrendered after the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August. The Hiroshima attack killed perhaps 80,000 people, and it ended the war with Japan.

In human terms, World War II was even more costly than the first conflict. Perhaps 60 million people died, or 3 percent of the world’s population. This time, most of the casualties were civilians. Weapons such as bombers and rockets brought warfare into the centers of cities. Mobilization for war was even more “total” than in the first war, particularly in Germany and the Soviet Union. The horror of the war found its most potent symbol in the Nazis’ systematic murder of 9 million people, 6 million of them Jews.

Humans and Ideas

Despite crisis after crisis, Big Era Eight brought new creativity to science, the arts, popular culture, and political and social thought. Communism, fascism, and new liberation movements opposed to European imperialism severely challenged the liberal ideologies of Europe and the United States. Even for many citizens of European democracies, the horrors of war seemed to discredit the liberal ideology that had seemed so full of promise in the late nineteenth century. The historian Oswald Spengler, for example, captured this mood in a work called The Decline of the West, which he first published in 1918. The book, which became a bestseller, argued that all civilizations rise and fall and that World War I marked the beginning of Europe’s decline. To many, liberalism seemed only a veneer that protected exploitative and incompetent governments and allowed social and economic inequities in the world to continue. On the other hand, the US, Britain, and several other European countries mobilized millions of citizens for war without compromising their democratic institutions very much. In fact, these nations broadened the base of popular participation in civic life, notably to include women.

Science and art. The challenges to nineteenth-century traditions extended to science and the arts. Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg, and other scientists developed the theory of relativity and quantum physics in the first three decades of the twentieth century. They both undermined Isaac Newton’s model of a fixed and predictable universe, which scientists of the nineteenth century had taken for granted. In psychology, Sigmund Freud showed the power of irrational forces that lurked in the human sub-conscious. In the fine arts, a mood of anti-rationalism and pessimism brought forth new genres of art. More extensive cross-cultural exchanges of artistic ideas challenged established artistic traditions in most parts of the world. For example, West African wood sculpture inspired the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), and Mongolian artists incorporated traditional motifs into contemporary art forms such as photography. Entirely new art forms, such as motion pictures, radio drama, and jazz blurred the lines between elite and popular culture.

German radio made by the Telefunken company in 1931. World Images Kiosk, San Jose State University http://worldimages.sjsu.edu ©Kathleen Cohen |

|

|---|

Mass communication and popular culture. Perhaps for the first time in history, popular culture, instead of being just the cultural heritage of a particular region, began to reach around the globe. Soviet leaders deliberately used cinema to spread their socialist message to rural villages. In doing so, however, they also ensured that Soviet movie-goers would learn about Hollywood and American values. Radios gave leaders access to vast audiences, and gifted speakers such as Roosevelt, Hitler, and Churchill used the new medium to mobilize whole nations for war. The popular press helped spread new political messages, including fascism and communism, while giving people in democratic societies broader and quicker access to information about the world. Nationalist leaders in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia became increasingly skilled at using newspapers and radio to build mass support. The new media also helped popularize sports such as football and baseball. Refined cultural tastes and values, once the preserve of elite groups, spread increasingly among the working masses.

The world of 1950 was very different from the world of 1900. It was a world disillusioned with nineteenth-century hopes for progress, no longer politically and economically dominated by Western Europe, more populous, more urbanized, and more productive. The world of 1950, however, was just as divided and conflict-ridden, and it bristled with dangerous weapons unimaginable in 1900. In the aftermath of World War II, it was not at all certain that humans could find a way of living with the terrifying technological powers unleashed by the Industrial Revolution. Could peace be preserved better in the second half of the century? Could the machinery of economic growth reduce the global inequalities that had helped fuel the conflicts of 1900-1950? Or was the world doomed to ever more destructive conflicts as power groups fought over the wealth that the technology and science of the modern revolution had generated?

Teaching Units for Big Era Eight

Definition of Panorama Teaching Units

8.0 |

Turbulent Decades |

PowerPoint Overview Presentation: |

Complete Teaching Unit Download Options:

|

Definition of Landscape Teaching Units

8.1 |

The causes and consequences of World War I |

||

|---|---|---|---|

8.2 |

The search for peace and stability in the 1920s and 1930s |

||

8.3 |

The Great Depression |

||

8.4 |

Nationalism and Social Change in Colonial Empires |

||

8.5 |

The causes and consequences of World War II |

||

8.6 |

Revolutions in Science and Technology |

||

8.7 |

Environmental change: The great acceleration |

Definition of Closeup Teaching Units

3.2.5 |

Korea |

Footnotes:

1 J. R. McNeill, Something New under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World (New York: Norton, 2000), 283.

2 Maddison, World Economy, 262.

3 Maddison, World Economy, 262.

Note:

Documents in Portable Document Format (PDF) require Adobe Acrobat Reader 5.0 or higher to view, download Adobe Acrobat Reader.

Documents in Powerpoint format (PPT) require Microsoft Viewer, download powerpoint.

Documents in OpenOffice format (ODT) require Oracle OpenOffice, download Oracle OpenOffice.

Documents in Word format (DOC) require Microsoft Viewer, download word.

|

World History for Us All is a project of the UCLA Department of History's

Public History Initiative, National Center for History in the Schools. Project Support | Conditions of Use |