Home > Key Themes > Seven

Key

Theme 7: Spiritual Life and Moral Codes |

|

|

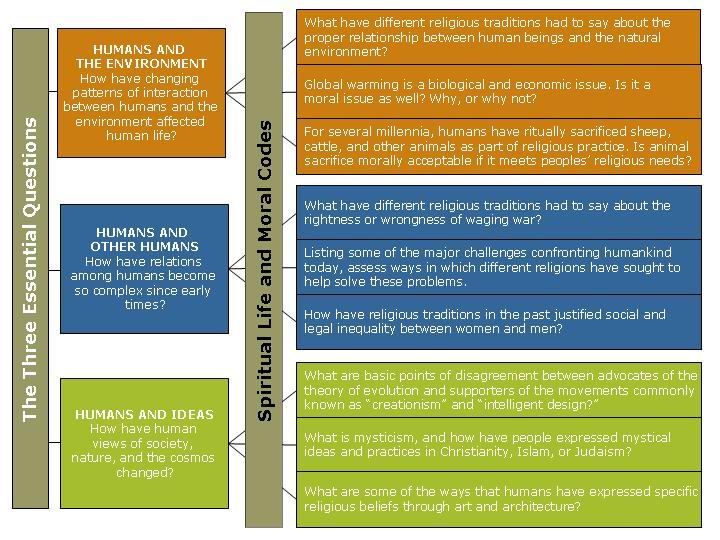

Are morality and spirituality unique to human beings? How

has human spirituality changed in the course of history? How

have changing ideas of morality and spirituality shaped history?

The word spirituality refers to human awareness of a transcendental

state of being, one that is beyond the material world of everyday

life. It may mean belief in a supreme creator, in an afterlife,

or in the existence of mysterious spirits and magical forces.

Our sense of spirituality shapes how we think of the world

and our place in it. It also shapes our sense of morality,

that is, the way in which we recognize differences between

right and wrong. Spirituality has been a powerful force in

human history.

Do animals have a sense of spirituality or morality? All

animals have to learn that some behaviors work well and others

do not. A young deer that strays too far from its herd may

be “punished” by being killed. Those who learn

these rules of behavior survive. Those who do not learn them

may die.

We have no evidence, however, that animals think in moral

terms, no sense that they are aware of doing “good”

things or “bad” things. Being aware of morality,

like being aware of identity (Key

Theme 5), appears to be uniquely human. Only we humans

have language, which allows us to think about the rightness

or wrongness of our behavior. The same is probably true of

spirituality. Symbolic language allows us to express and share

information, not just about what is in front of us, but also

about things that we cannot see with our eyes or hear with

our ears. Language lets us think and talk about God, angels,

saints, demons, fairies, heaven, and hell. Only humans, it

seems, can imagine a spiritual realm.

As far as we know, all human communities have had ideas of

a spiritual realm and of rules for right and wrong behavior.

Different communities, however, have thought about those things

in an astonishing variety of ways. People have often fought,

killed, or died to put forth or defend their own ideas of

spirituality and morality. A belief or practice that one community

considers normal may seem totally unacceptable to another.

For example, in some communities people have traditionally

regarded public nudity as normal. In others, they have seen it

as shocking and offensive.

What can we know of the spiritual life of our distant ancestors

in paleolithic times? Archaeologists have found many objects

that look as if they had spiritual meaning to those who created

them. Fifteen thousand years ago, people in southern Europe

took the trouble to crawl far back into the dark reaches of

a cave to carve clay statuettes of bison that hardly anyone

was ever likely to see. We do not know why they did this but

certainly not merely to amuse themselves or to make "art

for art's sake." What about cave paintings that show

hunters stalking animals? Were these works possibly designed

to cast a spell over animal prey? One cave painting includes

the picture of a man who looks to modern eyes like a priest

or wizard. We do not really know if he was or not. The problem

is that we know so little about the wider social or cultural

contexts in which works like these were produced and used.

We do have some ideas, however. Anthropologists have studied

the spiritual beliefs of small, relatively isolated communities

that exist today. Scholars of paleolithic history base many

of their ideas about early human thought and behavior on such

studies. In many of these communities there may be no clear

borderline between the human and spiritual worlds. One feature

that seems to appear in all small-scale communities is animism.

This is the belief that the world is full of spirits and that

to survive one must coexist and communicate with them. One

must pray to them, bargain with them, and even try to ally

with them in disputes with human or non-human enemies.

The community may regard natural objects and forces, such

as rain, wind, thunder, trees, the sun, the moon, and stars

as members of a huge and varied family. People, however, may

not always think of spirits as more powerful or more moral

than humans. Spirits may be like family members. Some are

good and helpful, and some are bad, fickle, dangerous, or

stupid.

In some parts of the world societies have totemic beliefs,

that is, ideas about close spiritual ties between families

or clans and particular animals. The members of a “jaguar

clan,” for example, might forbid killing jaguars because

of the belief that these animals are in some sense also part

of the extended family.

How did people contact the spirit world? They might hear

spirits in a thunderstorm, or they might make contact through

dreams or rituals. Religious ceremonies might involve dancing,

chanting, or taking mind-altering drugs to induce a trance-like

state and a feeling of “crossing over” to the

spiritual realm. Frequently, communities looked for help from

individuals believed to have special gifts for communicating

with the spirits. In Siberia and some other parts of the world,

such specialists have been known as shamans. These are women

or men who have the power to go into a trance. In that state

they may “fly” to the spirit realm to talk, fight,

or plead with spirits—even to marry them. Upon returning

to the human world, shamans tell other people what happened.

Their pronouncements may have a powerful effect on people,

curing their diseases, cursing them, driving them to war with

their neighbors, or encouraging them to make peace. A shaman

could be an extremely powerful man or woman in a community.

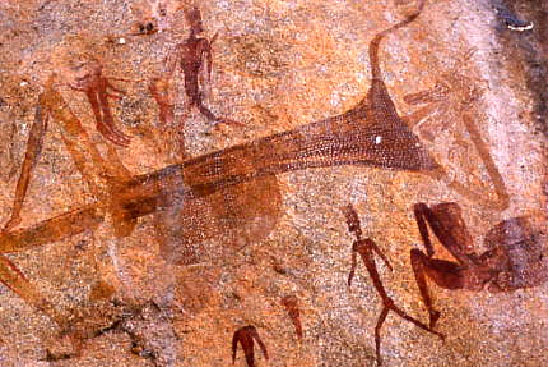

Hunting and foraging

people painted this rock art in Zimbabwe in Southern Africa

about 2,000 years ago.

The scene depicts a

ceremonial dance whose purpose may have been to animate the

life force.

The large figure in the center, very likely wearing an antelope

mask, is lying down

and perhaps in a state of trance, or altered consciousness.

“ Diana’s Vow" site, Manicaland, Zimbabwe

R. Dunn

In small-scale societies, most spirits were

local, and people identified strongly with particular ones.

After about 12,000 BCE, however, larger-scale societies began

to appear. When that happened, people’s sense of spirituality

also changed. As communities became larger and more powerful,

their gods, too, became more potent and awe-inspiring. These

deities were often venerated beyond the local community.

Priests and rulers began to take on the power that shamans

once exercised. Rulers of city-states and kingdoms that existed

5,000 or 6,000 years ago often claimed spiritual power and

identified themselves with particular gods. In Sumer in lower

Mesopotamia (the Tigris-Euphrates River valley), each city

had its own major deity, which people represented in images

of stone or wood. For example, in the city of Uruk the goddess

of love, known as Inanna, inhabited the “white temple.”

This building stood atop a ziggurat, or stepped, pyramid-shaped

structure, which dominated the whole town.

In Sumer every urban temple had its religious leaders, or

priests, who had the job of pleasing the gods in endless rituals,

festivals, and sacrifices. People dedicated all their labor

to the service of the city’s gods. Therefore, the priests

claimed the right to command the population and economy, ruling

the city as the top social class. Religious teachings supported

the right of the city-state’s rulers to accumulate wealth

and wield power. Priests instructed ordinary people that,

if they wished to receive the blessing of the gods, they should

obey their rulers. The priests might try to dull people’s

willingness to protest against abuse and exploitation by threatening

them with the wrath of the gods or by promising them a better

life in the afterworld if they remained obedient.

In the third millennium BCE, when bigger states began to

appear, rulers almost always associated themselves with the

most powerful deities. In ancient Egypt or the later Roman

empire, for example, rulers claimed to be not only the deputies

of gods but deities in their own right. In the ancient Mediterranean

region and other places, people thought of their numerous

gods and goddesses as part of a pantheon, or “household”

of deities that controlled the universe as one big and sometimes

quarreling family. Stories about the gods were at the heart

of oral and literary traditions, and children learned about

duties and obligations, right and wrong behavior, from the

examples that gods and goddesses set.

In Afroeurasia in the middle centuries of the first millennium

BCE, belief systems began to appear that eventually became

world religions. These systems focused on a single supreme

god or cosmic, creative power. They also appealed to people

of differing languages and cultural traditions, not just the

members of a single city or local area. Most of these systems,

though not all, were “universalist” in that they

preached their message to whomever would listen, not just

to particular groups.

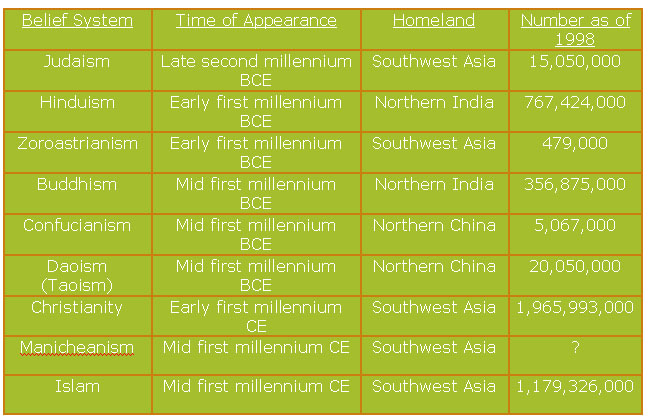

The major universalist religions to appear so far—all

of them by the seventh century CE—have been Hinduism,

Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity, Manicheanism, and Islam. Among these,

Hinduism has remained closely associated with South Asian and,

to some extent, Southeast Asian societies. People have practiced

Daoism mainly in China. Confucianism also emerged in the mid

first millennium BCE, but as a belief system it has emphasized

moral and ethical behavior much more than spiritual doctrines.

Also, it has remained firmly linked to East Asian societies,

especially Chinese. Judaism, which took shape as a distinctive

belief system in the first millennium BCE, shared its monotheism,

or belief in one God, with Christianity and Islam. Jews, however,

did not take up a universalist mission but rather have transmitted

their faith mainly within the community believed to descend

from the early Hebrews.

Today, more than 70 per cent of the world’s population

identifies at least nominally with Buddhism, Christianity,

Islam, or Hinduism. In the past millennium, however, Manicheanism

has faded from global view, and Zoroastrians (called Parsis

today) number fewer than 500,000.

Table data from Ninian Smart,

ed., Atlas of the World’s Religions

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 13.

All the world religions embrace varying beliefs,

practices, and sects. None is homogeneous or uniform. For

example, in Islam, Sunnism and Shi’ism constitute two

major branches with somewhat differing beliefs. In fact, the

Shi’ite tradition has several branches of its own. In

the Christian tradition Roman Catholics, Greek Orthodox Catholics,

Protestants, and other groups all share basic monotheism but

with numerous differences in doctrine, ritual, and practice.

Most major religious traditions also incorporate two important

dimensions. One of them involves people joining together for

public worship, communal prayer or ritual, scriptural study,

and mutual moral and social support. The other, which in some

traditions is characterized as mysticism, is concerned with

the individual’s search for knowledge of God, union

with the divine, transcendent experience, healing, and salvation.

For millions of people, religious experience may involve both

of these dimensions.

A final point about the varieties of religious experience

is that people in many parts of the world, and in rural areas

more than in cities, have professed one of the major religions

but assimilated older animist beliefs into it. For example,

a Christian community might honor a local saint who is a Christianized

version of an ancient god or spirit. For another example,

Muslims in some places wear a little box around their neck

with a piece of paper in it carrying an inscription from the

Qur’an. They display this charm, or amulet to ward off

evil, even though Muslim scripture does not condone such a

practice.

The architecture of Christian churches

varies greatly depending on the denomination and the region.

On the left is a Methodist chapel in Wales. On the right

is ancient Greek Orthodox church in Istanbul, Turkey.

R. Dunn

Today, many people argue that modern science

presents a powerful challenge to religion because it offers

explanations of nature, the cosmos, and human origins that

require no reference to God or any other manifestation of

spiritual power. Also, the material evidence that science

presents to support its description of the natural and physical

universe has continued to pile up, especially during the

past century. Few doubt that science, technology, and medicine

have benefited humankind in countless ways. For some people,

however, science and religion start from such contradictory

premises that they cannot be reconciled. This perceived

contradiction may even be a source of profound bewilderment

or dismay. Other people, however, find no trouble accepting

the propositions of modern science while at the same time

expressing faith in a transcendent creative power.

Principles and standards of ethical behavior

are as important to peace, order, and social cooperation

in the world as they have ever been. Science, however, has

very little to tell us about ethics. Also, persistent poverty,

environmental degradation, epidemic disease, and crime have

defied the best efforts of humanity’s scientific imagination.

Amid the distresses and dangers of our contemporary era,

people have sought not only communal ties to one another

but also moral and spiritual certainties. Spiritual quests

and ethical questions continue to be a vital part of human

cultural

Why Do We Need to Understand this Key

Theme?

-

For most of human history, spiritual

ideas have been at the core of how humans understand and

explain the workings of the natural, physical, and social

world. No wonder that people have stood up, and sometimes

died, for their religious principles, or that societies

have built their sense of unity and identity around their

spiritual traditions. How people explain the world and

find meaning in it shape their hopes, fears, and behavior

toward one another. Young people who struggle today with

spiritual questions and uncertainties should understand

how and why these yearnings have always been among the

most powerful shapers of the human past.

- Human beings learned long ago that peace, order, and cooperation

within social groups, whether they be families, foraging

bands, business partnerships, or nation-states, depend in

the long run on guiding principles, standards, and rules

of moral behavior. Systems of morality and ethics vary around

the world, but all of them are founded on ideals of social

harmony and trust. Moreover, successful collective learning

among human communities requires forthrightness, honesty,

and trust between both individuals and groups. Belief systems

embody the shared moral and ethical expectations that allow

humans to get along in peace and to learn systematically

from one another.

Landscape and Closeup Teaching Units that Emphasize

Key Theme 7:

[In Development]

|